The Alvin Ailey American Dance Company is accredited with breaking down barriers to persons of colour in concert dance throughout the mid to late 1900s. Alvin Ailey, the man behind it all, utilized his life experiences to completely transform the Black experience in dance and invite audiences to a world in which black bodies are celebrated.

I am trying to show the world we are all human beings, that colour is not important, that what is important is the quality of our work, of a culture in which the young are not afraid to take chances and can hold onto their values and self-esteem, especially in the arts and in dance. That’s what it’s all about to me”

–Alvin Ailey

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. (n.d.). Mission and Core Values. Alvinailey.org. https://www.alvinailey.org/about-us

The Beginnings of a Black Boy

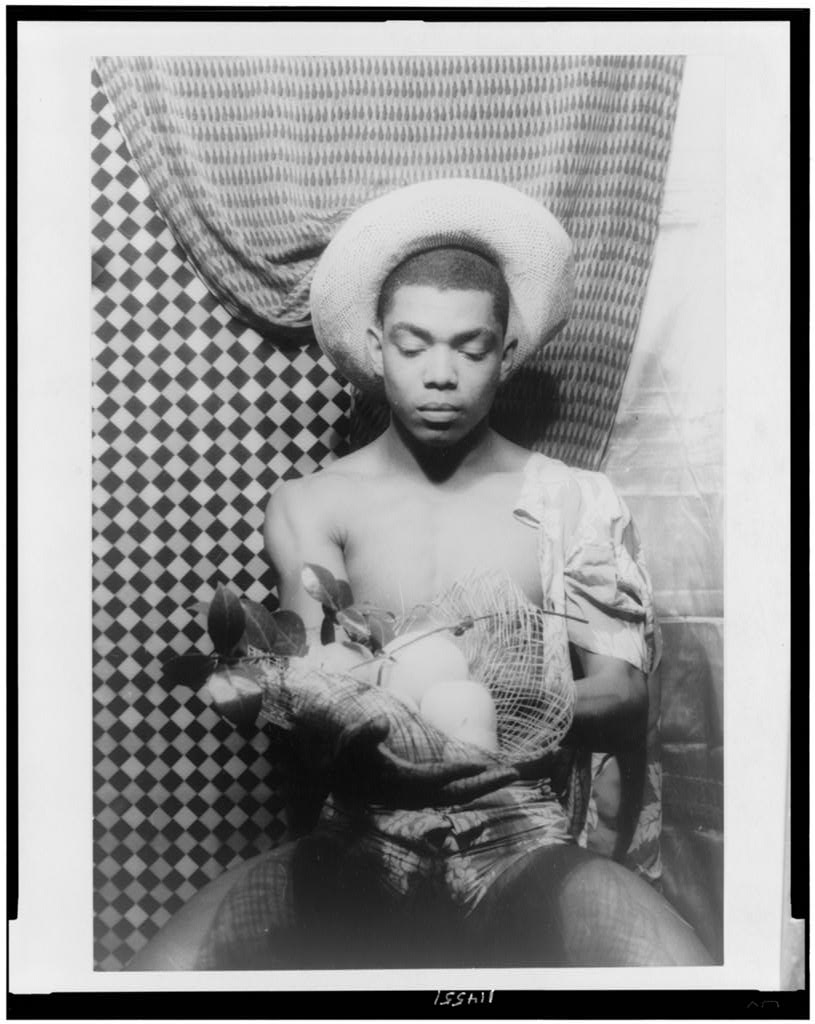

On January 5th, 1931, Alvin Ailey was born in Rogers, Texas during a time of poverty, struggle, and segregation. Ailey’s parents separated when he was only an infant, and his mother worked hard every day to provide him with the best life possible. As a result of the job market, Ailey and his mother continuously moved around. However, wherever they went, Alvin Ailey, a young Black boy, was taught about what his skin colour meant to the world. Texas during these years was highly segregated, and Ailey was consistently exposed to the hostility expressed towards African Americans throughout his childhood. Negative experiences, like the rape of his mother by a white man when he was only five years old, contributed to a swarm of rage and pain towards the socially perceived inferiority of his race that he would later direct into his work. Although Ailey was inspired by art and the blues from a young age, his acuity for dance only manifested in 1942 when he and his mother moved to Los Angeles.

A Dancers Fate

In Los Angeles, Ailey’s race did not disappear. The Ailey’s originally lived in a white area, but Ailey complained to his mother that they “did not know what to do with a black student” at his school, so they moved to a more diverse neighbourhood. Along with the immense culture and diversity the city of Los Angeles had to offer, Ailey’s new schools provided him with his first views of positive attitudes towards African Americans and their abilities. The pain Ailey carried from his youth in Texas followed him to LA, but he found solace and comfort in the world of theatre and dance. As Ailey’s appreciation and love for dance grew, he was simultaneously discovering his sexuality and experiencing a whole new type of discrimination. As not only a Black man, but a Gay Black man, Ailey was subjugated to further isolation because of these intersecting identities. In 1949, Ailey was introduced to Lester Horton: a gay, white, choreographer and dancer who was revolutionizing dance by experimenting with various modern styles and promoting a multicultural environment. Ailey was inspired by Horton, and spent many years with Horton’s school where he performed his first solo (Revue Le Bal Caribe) and choreographed his first piece (Afternoon Blues) at just 22 years old.

Ailey found serenity and safety in dance, and he described it as a “release from heterosexual white hegemony” (DeFrantz, 2004). When Lester Horton suddenly passed in late 1953, Alvin Ailey stepped up to take over the school. Despite barely two years of dancing experience and only one piece of choreography under his belt, Ailey began creating choreographic masterpieces, directing massive dance scenes, and producing beautiful costume and set designs.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre

In the early part of 1958, Alvin Ailey departed LA and Horton’s school to form the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre in New York City. Ailey believed his dances, and therefore his company, encompassed both the best and the worst parts of every American life –hence the name Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. Ailey and his troupe’s debut took place later in 1958 through a massive program that was critiqued as overwhelming and poorly executed (DeFrantz, 2004). Ailey did not care for these critiques, because along with the unprecedented scale of his premiere, he expressed one clear message loud and true:

“The Black body has unquestionable capabilities and undeniable power in concert dance.”

DeFrantz T. (2004). Dancing revelations: Alvin Ailey’s embodiment of African American culture. Oxford University Press.

Ailey continued as a director, dancer, and choreographer for his company until 1965 when he took a step back from dancing. To expand his reach, Ailey established what is now known as The Ailey School in 1969 and Ailey II in 1974. Unfortunately, Alvin Ailey could not revel in all the success that would come his way. In the 1980’s, Ailey was suffering from a condition now known as bipolar disorder. Even through hospital visits and episodes of mania, or rehab treatments and all-consuming addictions to alcohol and cocaine, Ailey never stopped working and choreographing for his company.

Sadly, Alvin Ailey passed away on December 1st, 1989, due to an AIDS related blood-disease. As a Black Gay man, he refused to release this information for fear of social backlash and insisted no one know he passed from AIDS. Despite only 58 years in this world and a mere 36 years in the dance world, Ailey made significant changes and left a long-lasting impact on both the Black and the Dance communities.

Ballet in White

Alvin Ailey was inspired by the beauty and technicality of Ballet and drew from it in many works. Ballet, a dance style completely based in white colonialist values and ideals, created tension within both Ailey and his Black dancers, resulting in a constant battle with the inherent structure of ballet and dance itself. Sekani Robinson (2021) explains:

“Ballet has been an exclusive, white elite space that mirrors history in that it is perceived through a dominant white culture which has ignored, marginalized, and excluded Black bodies. Like a great deal of culture in the United States, American ballet [is] highly influenced by Black culture and Blackness, stolen and appropriated by white Americans while Black bodies remained devalued and excluded.”

Robinson, S. (2021). Black ballerinas: The management of emotional and aesthetic labor. Sociological Forum, 36(2), 491-508. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12689

The dominant white culture Robinson refers to is the “persistent focus on whiteness in the ballet” (Kerr-Berry, 2016; Robinson, 2004). Even though American ballet was highly influenced by African culture at this time, the European ideals and aesthetics were considered elite in the eyes of society (Kerr-Berry, 2004). To be a prima ballerina, a dancer must display elegance, beauty, and fragility– all of which seen to be embodied by the white female and contrasted by the black female (Kerr-Berry, 2004). Moreover, it is extremely evident that current media projects the whiteness of ballet and emphasizes the image of a “perfect ballerina” to be a beautiful, white girl in a pristine tutu, as depicted in the picture above. Regardless of ballet being a historical collaboration of European and African cultures, the structural whiteness of dance and ballet create immense barriers for all dancers who do not fit the “white” mould (Kerr-Berry, 2016).

Barriers in Black

Robinson (2021) conducted a study that reveals the extremely high prevalence of Black ballerinas who feel rejected and out of place in the dance world.

Like many of the dancers of Ailey’s time, the ballerinas in this study complained of the aesthetic discrimination they faced through limited diversity in leotards and pointe shoes. Leotards and pointe shoes were each created with a clear purpose: to cultivate a uniform picture and to lengthen dancers’ lines. However, Black dancers often must conform to white ideals as there are almost no pointe shoes or leotards manufactured in a variety of natural skin tones that diverge from the European complexion– as this is seen as the pinnacle of a beautiful ballerina (Robinson, 2021; Rodriguez, 2021; McCarthy-Brown, 2011; Johnson, 2017).

As a result of having limited options for their “uniforms,” Black dancers often resorted to staining their own tights, leotards, and pointe shoes, to regain the smallest amount of comfort (Johnson, 2017). The utter disregard for the needs of dancers of colour continues to reinforce racial hierarchies that privilege the white (Robinson, 2021; McCarthy-Brown, 2011; Rodriguez, 2021).

Another major form of discrimination against Black dancers comes in the form of typecasting and colour casting (Robinson, 2021; McCarthy-Brown, 2011; McCarthy-Brown & Carter, 2019). Typecasting is done with the use of controlling images which are defined as “images of subordinate group[s] developed by a dominate group that work to justify oppression” (Robinson, 2021). Black dancers are often subjected to roles in dance that are deemed to be appropriate for them based on stereotypical views and opinions of the Black population that have manifested as a result of dominant white culture (DeFrantz, 2004; Robinson, 2021; McCarthy-Brown, 2011; Rodriguez, 2021). Similarly, colour casting assigns dancers to roles based on the complexion of their skin. Meaning, if a person of colour has a lighter skin tone, they will often be chosen over their darker counterparts for roles as they are a closer representation of a true dancer, as depicted by whiteness (Robinson, 2021; McCarthy-Brown, 2011; Rodriguez, 2021). These ideas force a dichotomy of white as the ideal of beauty, and Black as everything opposing it.

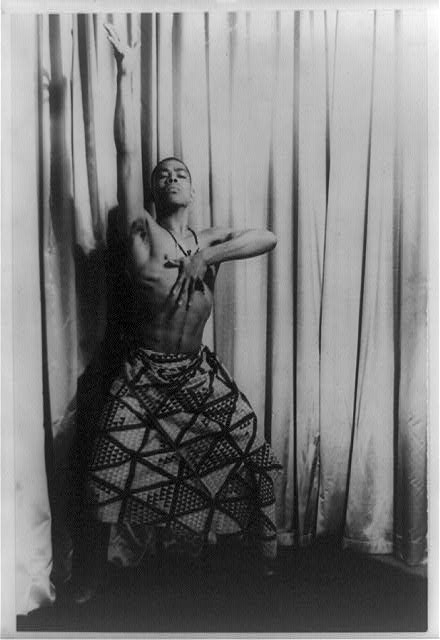

In ballet, Black women are commonly subjected to side-roles of an exotic, sexual, or submissive nature, whereas Black men are placed in roles that display super masculine qualities, and both men and women of colour are rarely given primary roles. These controlling images used to typecast Black men and women in ballet perpetuate the idea that Black bodies are not built for this style and are unable to perform in the nature ballet dictates aesthetically and technically (Robinson, 2021).

Interestingly, Alvin Ailey utilized these common practices of typecasting and objectification with his Black dancers as a tactic to gain further success and break down barriers (DeFrantz, 2004; Nii-Yartey, 1991). In a seemingly backward manner, Ailey worked to satisfy his audiences racialized ideals and by doing so, he was able to undermine negative perceptions of Black bodies (DeFrantz, 2004; Nii-Yartey, 1991).

“This double-edged effect allowed white audiences access to glamourous black bodies in heightened states of grace, whether those audiences viewed their efforts as aesthetic, erotic, or more likely, a combination of the two. Black bodies on display seem[ed] to enact this duality by virtue of Americas peculiar history.”

DeFrantz, T. (2004). Dancing revelations: Alvin Ailey’s embodiment of African American culture. Oxford University Press.

Therefore, by appeasing societies’ need to see Black bodies in a particular light, Ailey was also able to, almost silently, challenge their views of bodies in dance and provide inspiration to people of colour in the dance community (DeFrantz, 2004). Even though the world did not know it at the time, Alvin Ailey would become one of the leaders of a revolution in dance where the Black body was not only appreciated, but valued and considered an accurate portrayal of Americans on stage.

The Battle Continues

The discrimination and racism within the institution of dance is rooted in one primary problem: those who are privileged by whiteness fail to see the detrimental repercussions to those oppressed by this ideology and system. (McCarthy-Brown & Carter, 2019). As a result of those who uphold whiteness as an ideal, the oppression of Black dancers and dancers of colour continues to be sustained and misunderstood. Although Ailey broke into the dance world, and his company has continued to challenge many perceptions of Black dancers, these problems are still extremely prevalent for dancers of colour today.

Given the strong resistance to acceptance, influential leaders in dance must continue to protest misconceptions of Blackness as it relates to dance both physically and culturally. The conversation of racism in dance can be incorporated into the form of dance itself, not only to allow the expression of the black dancers’ experiences, but to provide a platform and language in which white dancers can understand the difficulties and barriers facing people of colour (McCarthy-Brown & Carter, 2019). As McCarthy-Brown and Carter (2019) states, dancers use their bodies to “investigate, create, and perform the realities and imaginations of the human experience,” so why not integrate anti-racist practices and messages in these spaces?

Alvin Ailey took major and important steps in combatting racial injustice in both ballet and modern dance. The legacy of Alvin Ailey lives on through the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, where young Black dancers continue to be inspired by his incredible story. Alvin Ailey may have started the fight, but the war for equality and equity in dance is far from over.

Resources

Below are some resources of interest on the various topics discussed here. The first step in anti-racism efforts is to further educate ourselves on the discrimination present in dance and then we can take action and continue Alvin Ailey’s Legacy of inclusion and inspiration.

Alvin Ailey & Company

Below are resources to learn more about Alvin Ailey, his legacy, and the company he left to continue his mission.

Information about Ailey and his company can be found at: https://www.alvinailey.org/

Dancing Revelations by Thomas DeFrantz is an amazing read that deconstructs Ailey’s entire career and legacy to analyze the implications of race and sexuality on Ailey and his life’s works.

Ailey, a documentary by Jamila Wignot, dives into Ailey’s life and the mark he left on the dance world.

Learn more about the various educational and preforming opportunities at the Alvin Ailey American Dance theatre.

Discrimination & Dance

Below are resources to help educate yourself on various forms of discrimination against persons of colour in dance.

Dance Pedagogy for a Diverse World by Nyama McCarthy-Brown provides tools for integrating diverse teachings and combatting institutional racism in dance.

Radicalizing Dance by dancer and activist Rodney Diverlus provides a first-person view of discrimination in dance.

The Black Dancing Body by Brenda Gottschild highlights the history of discrimination in dance.

How Ballerinas of Color are Changing the Palete of Dance by Rohina Katoch Sehra shares stories of BIPOC ballerinas making change.

Taking Action

Below are resources to help in your pursuit of action and ideas to help promote change.

Some commonly experienced forms of discrimination that reinforce systemic racism in dance can be read here.

A brief summary of ways to respond to microagressions.

Ballet Creole is a Canadian Professional Black Dance company promoting diversity and inclusion, read more about their initiatives on their website.

The Nia Centre for the Arts provides a space to educate, mentor and showcase Black Art.

Dance Immersion produces, promotes, and supports Black dances and dancers.

A comprehensive list of anti-racism educational tools can be found here.

References

DeFrantz T. (2004). Dancing revelations: Alvin Ailey’s embodiment of African American culture. Oxford University Press.

Johnson, O. (2017). The black sheep is the black dancer. Dance Major Journal, 5. https://doi.org/10.5070/D551036259

Kerr-Berry, J. (2004). The skin we dance, the skin we teach: Appropriation of black content in dance education. Journal of Dance Education, 4(2), 45-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2004.10387255

Kerr-Berry, J. (2016). Peeling back the skin of racism: Real history and race in dance education. Journal of Dance Education, 16(4), 119-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2016.1238708

McCarthy-brown, N. (2011). Dancing in the margins: Experiences of African American ballerinas. Journal of African American Studies, 15(3), 385-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12111-010-9143-0

McCarthy-Brown, N., & Carter, S. (2019). Radical response dance making dismantling racism through embodied conversations. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 20(13). http://doi.org/10.26209/ijea20n13

Nii-Yartey, F. (1991). Alvin Ailey a revolutionary in dance: A historical and biographical sketch of his choreographic works. In K. A. Opoku, A. Boaten, et al. (Eds.), Institute of African Studies: Research Review (pp. 87-92). Institute of African Studies of the University of Ghana.

Robinson, S. (2021). Black ballerinas: The management of emotional and aesthetic labor. Sociological Forum, 36(2), 491-508. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12689

Rodriguez D, M. A. (2021). Performing Whiteness: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Racism in Ballet [Student thesis, DiVA. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-177980]

*Cover photograph by Carl Van Vechten in 1966