What defines Canadian culture? Most people’s initial thoughts are represented through the sport of hockey. As Canada has an extensive history with the sport and claims it to be its own, and hockey has become a defining feature of Canadian culture. Nevertheless, the birthplace of hockey within Canada remains a widely disputed and complex area of research. However, hockey in Canada remains to go beyond the sport and is supported like an identity. In Canada, the associated culture is almost inescapable, and it is accepted that Canada and hockey are frequently associated (Cairnie, 2019). In addition, through Canada’s designation as a cultural mosaic, there are the assumptions that the national game would mimic similar traits of inclusivity, diversity, and quality (Sandrin, 2020). However, hockey within Canada is a very ‘white’ dominant sport. As a result, minority players face consistent discriminatory and racial actions, especially when a person of colour fulfills a role normally filled by a white person (Szto, 2016). Therefore, it is important to acknowledge that even though hockey is identified as Canada’s culture. It is even more important to acknowledge how colonization and racial discrimination have impacted Indigenous athletes’ levels of participation within the sport at both amateur and professional levels. An athlete that will be highlighted in this post is Everett Sanipass, an Indigenous professional hockey player that had a notable career within the NHL. Important to highlight, on his journey to the NHL, he experienced racial discrimination. However, Sanipass’s lesser-told story illustrates the importance of strength and perseverance.

Who is Everett Sanipass?

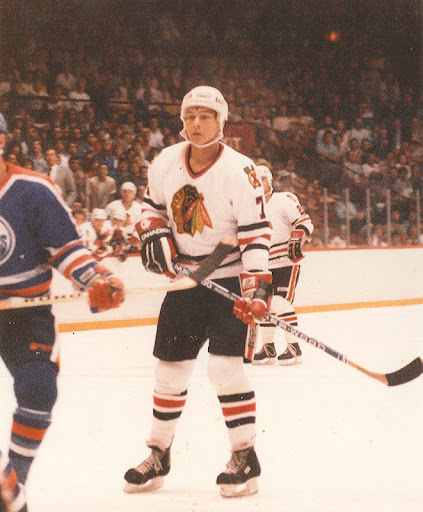

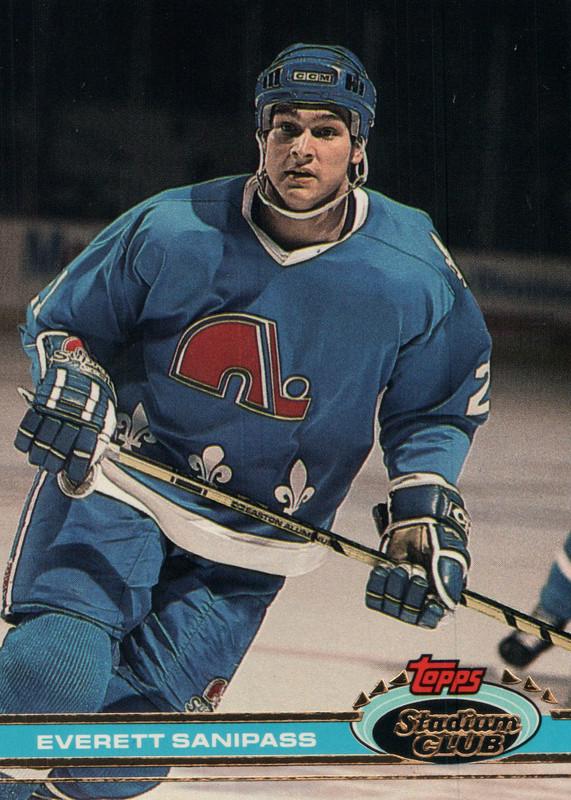

Everett Sanipass was born in his community of Elsipogtog First Nation, located in New Brunswick. Sanipass is a proud Indigenous person and is Mi’kmaq. Mi’kmaq is the First Nation people who exist within the Eastern provinces of Canada. Being Indigenous, Sanipass was subjected to experience racial discrimination, and within his early hockey career, he experienced racism, as he was prohibited from playing on off-reserve teams. As a result, Sanipass and his family hired lawyers to address this injustice and to fight the racism (Joyce, 2006). Sanipass had a notable junior hockey career. It drew considerable attention after his season within the Brunswick Amateur Hockey Associated, scoring forty-three goals and twenty-six assists in only thirty-seven games. In 1984, Sanipass started to play in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL) with the Verdun Junior Canadians. After four seasons in the QMJHL, Sanipass was drafted 14th overall by the Chicago Blackhawks and resulted in him being the first Indigenous person drafted out of New Brunswick, where he spent four seasons with the Blackhawks and then was traded to the Quebec Nordiques, where he spent two seasons. Before Sanipass’s notable professional career, Sanipass had already been labeled a “tough guy” within the league. Before his NHL debut, he was a member of the Canadian U20 team, and within this tournament, there was a famous game between Canada and the Soviet Union. Within this game, both teams were ejected after a 20-minute fight broke out, and the official’s reactions were to turn the lights out to contain both teams. Sanipass’s experience with the Junior National Team resulted in him being susceptible to racial stereotypes that Indigenous hockey players experience.

History of Racialized Stereotypes and Underrepresentation

Historically, Indigenous peoples have been excluded from sport organized by colonizers. Colonizers have used racialized stereotyping of Indigenous people’s sports to demonstrate inferiority and illustrate intellectual superiority. Indigenous notions of masculinity were represented differently than colonizers (Cosentino 1998; Paraschak, 1989). In other words, the white majority has used racial stereotypes towards Indigenous culture through physical aggression. Although it has been found that some stereotypes are diminishing, the idea of “savage” continues to inform understanding of Indigenous cultures (King, 2005). Sanipass’s experience with the Canadian Junior National Team and the infamous game exemplifies racialized stereotypes. Sanipass is receiving “tough guy” labels within the league before even playing an official game. Likely, his white teammates did not receive such labels from their experience within the team brawl, and their tournaments were likely highlighted through goals scored and assists. As white athletes are typically praised for embodying positive values and characteristics and skills that demonstrate intellectual strength and dominance in comparison to minoritized athletes (Szto, 2021).

As mentioned, hockey has been traditionally known as a ‘white man’s sport.’ As a result, Indigenous athletes continue to be underrepresented. The underrepresentation may result from colonization and has impacts within lack of sports infrastructure, access to coaching, travel, equipment, and lack of financial stability (Forsyth, 2014). Additionally, the underrepresentation may be an outcome of racial stereotypes and discrimination. Sanipass’s experience within the NHL is unique as there is an underrepresentation of Indigenous athletes within the league. There are many reasons to explain why there is an underrepresentation, such as cultural and political resistance to hockey and the NHL. The resistance to hockey and the NHL could be rooted in the usage of hockey within the Residential schools. As sport within Residential schools was used as biopower to produce docile bodies while implementing self-discipline and self-control (Szto, 2021). As hockey within Canada has historically been utilized within colonization and used for systemic structures within the Residential schools (Mckegney & Phillips, 2018). However, sport also presented the opportunity to escape the abuse and exploitations that Residential school survivors experienced. Sanipass did not attend a Residential School, but this does not discredit the racial stereotype, systemic racism, and intergenerational trauma that Residential Schools have left with Indigenous communities. It is important in acknowledging the various barriers that Indigenous people experience, specifically within sport. As Sanipass, in his hockey career, he was subject to racism, which resulted in him requiring legal action to play on hockey teams that were off-reserve. Experiences such as Sanipass can exemplify the barriers and the limited opportunities for Indigenous athletes. In order for Sanipass to pursue a hockey career, it required him to access teams off-reserve to develop further as a hockey player, but racial discrimination was a major factor that would make this opportunity difficult.

Oka Crisis and Stacking

Within Sanipass’s career, he played two seasons with the Quebec Nordiques. Between his 1989-90 and 1990-91 season, the Oka Crisis was unfolding within a small town in Oka, Quebec. The Oka Crisis resulted from a land dispute over Mohawk land, and this dispute resulted in the Canadian government sending 2,000 police and 4,500 soldiers. The Mohawk activist protecting their land that was getting stolen from the Canadian government received much media attention. The media coverage that was received surrounding the Oka crisis resulted in blatant negative stereotyping of Indigenous peoples. A strong theme of the media coverage was the Indigenous people were angry warriors. The activist and other Indigenous peoples were depicted as a threat to an orderly society, strengthening society’s view of Indigenous people as savage (Joseph, 2012). The strong media coverage of the Oka Crisis and racial stereotyping aligned with the emerging trend of stacking and the usage of Indigenous athletes as an enforcer within the NHL.

Stacking is a concept where Indigenous players are either overrepresented or underrepresented in a team’s specific positions or roles (Joseph, 2012). The concept of stacking is fueled through racial stereotypes and discrimination; stacking fueled the belief that Indigenous people are of physical superiority and intellectual inferiority. Within the NHL, Indigenous athletes were subject to filling enforcer roles. Their role was to protect the talented players and also utilize them for monetary profit. Implementing an enforcer role, increase ticket sales, as physical violence would be a form of entertainment for the fans (Morra & Smith, 2002). Sanipass’s being an Indigenous person and playing hockey within Quebec while the Oka Crisis was unfolding would subject him to experiencing racism and microaggressions. Although there are no interviews with Sanipass in the news addressing the racism he experienced. I am fortunate to have a relationship with Everett Sanipass, and he shared stories that within his experience at the Nordiques, he experienced verbal abuse and was called racialized names fueled by stereotypes and discrimination. The verbal abuse that Sanipass experiences are rooted from the media portrayal of Indigenous peoples that was occurring during the Oka crisis, and additionally the history of colonization.

Future Direction

Sanipass’s story and many other Indigenous athletes are important to share and learn from, as they are examples of strength and perseverance through racial barriers. Participation in sport is important and creates diverse and inclusive spaces for all minorities to develop and grow. The future direction of youth sport is important to Sanipass, as mentioned I am fortunate to be able to call him a friend. I asked Sanipass, what advice he would give to Indigenous youth pursuing a sport?

“Always be proud of who you are and surround yourself with great support. Never Quit”

– Everett Sanipass

Indigenous youth today face many barriers in leading active and healthy lives within their communities. The barriers result in the youth being unable to pursue excellence within the sport. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has created Calls to Action for the government to take action in ensuring that there is long-term Indigenous athlete development and growth. As well, that Indigenous athletes get inducted within Sports Halls of Fame, and to provide public education that shares the national story of Indigenous athletes within sport (“Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the future”, n.d.). Finally, it is important in sharing lesser told stories of athletes, similar to Everett Sanipass’s. As it grants the opportunity to recognize and understand the impacts that colonialism has had on Indigenous peoples.

References:

Cairnie, J. (2019). Truth and reconciliation in postcolonial hockey masculinities. Canadian Literature, (237), 103-183.

Cosentino, F. (1998). Afros, Aboriginals, and amateur sport in pre-World War One Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association.

Forsyth, J. (2014). Aboriginal sport in the city: Implications for participation, health, and policy in Canada. Aboriginal policy studies, 3(1-2).

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.).

Joseph, J., Darnell, S & Nakamura, Y. (2012). Race and sport in Canada: Intersecting inequalities. Canadian Scholars’ Press.

King, C (2005). Native athletes in sport and society. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

McKegney, S., & Phillips, T. J. (2018). Decolonizing the Hockey Novel: Ambivalence and Apotheosis in Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse. Hockey: Challenging Canada’s Game–Au-delà du sport national, 97-109.

Morra, N., & Smith, M. D. (1996). Interpersonal sources of violence in hockey: The influence of the media, parents, coaches, and game officials. Children and youth sport: A biopsychosocial perspective, 142-155.

Paraschak, V. (1989). Native sport history: Pitfalls and promise. Canadian Journal of History of Sport, 20(1), 57-68.

Sandrin, R. (2020). Sour Grapes: Exploring the Experiences of Minority Hockey Players in Their Battles Against Racism. A Closer Look in Unusual Times, 19.

Szto, C. (2016). #LOL at multiculturalism: Reactions to hockey night in Canada Punjabi from the twitterverse. Sociology of Sport Journal, 33, 208-219. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1123/ssj.2015-0160

Szto, C. (2021). Lecture 3: Colonization. KNPE 397: Race, Sport, and Physical Cultures, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Szto, C. (2021). Lecture 6: Whiteness. KNPE 397: Race, Sport, and Physical Cultures, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada